Stress & the Stress Response.

Stress is an encroachment on your body’s life force. Your body does an absolute splendid job of maintaining the various systems that make up your life force within very narrow margins. The collection of your biological variables—the body’s temperature, blood sugar, bone mass, blood pressure, pH, skin pigment, adipose levels, heart rate, growth hormone levels, immune response, hydration level, oxygen content, etc.—are all kept within certain parameters, and this maintenance has been termed, “homeostasis”. In fact, this is what life is: The innate ability to withstand the natural forces of erosion. The environment within which you live is constantly trying to erode your biological systems. For example, if the ambient temperature grows cold, it will, if left unchecked, draw out your body’s heat. This encroachment is kept at bay as your body responds to this stressor, deploying several feedback loops to maintain your homeostatic internal temperature. Stress is a vital part of life. If there were no stress at all, you would be unable to deal with any changes in the environment and would effectively cease to be in this world that we know.

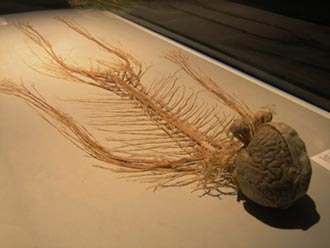

The body’s response to stress is elicited when system homeostasis is threatened—whether real or imagined. The intensity of the response is relative to the duration and intensity of the encroachment. The response is a cascade of neuroendocrine, neurotransmitters, cytokines, and growth factors that seek to mobilize energy and assist in restoring homeostasis. This action is mitigated through a negative feedback loop, which, similar to how your home’s thermostat operates, attempts to reverse a change in a variable. When the temperature of your home drops below the setting on the thermostat, sensors in the device send input to the furnace, switching it on to heat the air. When the air temperature then climbs above the setting, the device will send input to the furnace to switch off.

The body’s response to stress is elicited when system homeostasis is threatened—whether real or imagined. The intensity of the response is relative to the duration and intensity of the encroachment. The response is a cascade of neuroendocrine, neurotransmitters, cytokines, and growth factors that seek to mobilize energy and assist in restoring homeostasis. This action is mitigated through a negative feedback loop, which, similar to how your home’s thermostat operates, attempts to reverse a change in a variable. When the temperature of your home drops below the setting on the thermostat, sensors in the device send input to the furnace, switching it on to heat the air. When the air temperature then climbs above the setting, the device will send input to the furnace to switch off.

We may be able to say that environmental encroachments of very low intensity elicit little or no stress response and that the biological systems in place can correct the change. However, any system needs additional energy to work and one of the paramount functions of the stress response is to mobilize energy, so, perhaps the stress response is part and parcel of normal homeostatic function. As the stressor increases in intensity and/or duration, there is certainly a marked response of the stress system. For example, it is well known that a drop in blood sugar below normal levels—hypoglycemia—will elicit the stress response. However, under normal conditions, a slight drop in blood sugar “should” be corrected by the release a pancreatic hormone called glucagon, which acts on the liver, stimulating the release of glucose into the bloodstream. This is also one reason why fasting works well for some, not so well for others, and differently on the same individual at different times—the intensity of the associated stress response.

There is almost no function of the body that remains unaffected by the stress response. Arousal is heightened; sleep is reduced; metabolism, heart rate, and blood pressure are increased; growth and reproduction are halted; gastrointestinal function and digestion are inhibited; and the immune system and inflammatory response are enlisted. The body is primed to deal with the encroachment, and this is all part of a healthy functioning organism. However, as the duration of the encroachment lengthens, the stress response can change the function of the organism from normal and healthy to a pathological disease track. Hormesis is defined as a biological phenomenon that results in beneficial changes in an organism when exposed to low dose toxins for short time. This hormetic effect is none other than your body adapting to a stressor. Any stressor can be toxic if exposure is too intense and/or too long in duration. When the body adapts to a stressor in a beneficial way, with the associated stress response in retreat is called, “health”. The right amount of exercise has a hormetic effect; over-exercising leads to a diseased state.

Environmental encroachments—stress—affect us from everywhere, poor dietary choices, vehicular traffic, pollution, lack of exercise (or over-exercising), relationship friction, work obligations, etc; but the most intense of stressors in our modern society can affect us through our own mind. Psychological stress is an example of how the mind and brain (and body) are one. Something as seemingly benign as concern for an exam at school, or having an argument with your significant other, or socializing with new individuals can cause the same physiological response in the body as if fracturing a bone, or exposure to high heat. That is to say, something that doesn’t exist in reality—you create it in your mind—can cause a real event in the body. It is these psychological stressors that can wreak the most havoc on our system and degrade human health, however, the problem is compounded when psychological stress is coupled with physical stressors such as over-exercising, poor nutrition, poor oral hygiene, poor sleep hygiene, medical surgery, etc. So, in the context of worrying about your financial despair year in and year out, just a few cigarettes a day can finally result in disease.

Environmental encroachments—stress—affect us from everywhere, poor dietary choices, vehicular traffic, pollution, lack of exercise (or over-exercising), relationship friction, work obligations, etc; but the most intense of stressors in our modern society can affect us through our own mind. Psychological stress is an example of how the mind and brain (and body) are one. Something as seemingly benign as concern for an exam at school, or having an argument with your significant other, or socializing with new individuals can cause the same physiological response in the body as if fracturing a bone, or exposure to high heat. That is to say, something that doesn’t exist in reality—you create it in your mind—can cause a real event in the body. It is these psychological stressors that can wreak the most havoc on our system and degrade human health, however, the problem is compounded when psychological stress is coupled with physical stressors such as over-exercising, poor nutrition, poor oral hygiene, poor sleep hygiene, medical surgery, etc. So, in the context of worrying about your financial despair year in and year out, just a few cigarettes a day can finally result in disease.

Your ability to absorb stress, or your resilience to stress can be explained as a “biological bank account”. If you are constantly withdrawing from this account without depositing any currency, you will eventually show the signs and symptoms of system dysfunction and ultimately, disease. Because life is an ever-adapting force, a net withdrawal of your biological resilience can take years to present as dysfunction. Moreover, there are currently no accurate methods with which to measure the balance of this account. You can literally feel a strong physiological stress response to an encounter with a bear while out hiking on a trail, e.g., but there is no way to feel the low level of chronic stress that we all endure day to day. The eventual signs and symptoms are the only evidence of a drained account.

The symptoms of over-stress are largely individual; some folks will experience high anxiety and panic disorder, others will experience depression, others will accumulate body fat, some will avoid social situations, others still will suffer from frequent colds and illness, or migraine headaches. Attempting to seek relief from these symptoms, these individuals will seek medical care, that usually result in the use of pharmaceutical therapies, adding to the overall stress that the body must deal with. So, as one set of symptoms might abate, time might reveal a new set of symptoms, all with the same root cause—the encroachment(s).

If the body is over-stressed for a long while, it is devoting a lot of energy to merely keep you limping along. This energy must be diverted from another need: Exercise, organ function, immune capacity, etc. You might feel generally healthy; perhaps a little off, or maybe just tired… all the while there is vast concert being orchestrated underneath the surface that is trying to maintain homeostasis. The very base of human health, everything considered, is to manage your stress such that your biological account stays deep in the black. Stress management begins with the removal or reduction of as many of the controllable stressors in your life, e.g., improved nutritional choices, start exercising (or stop over-exercising), cease alcohol/tobacco use, etc. Stress management then continues with certain practices that enable you to change your attitude toward life to a more hormetic one. In other words, both physical and psychological stress needs to be attended to. Over time, your biological bank account will grow (you will heal) and your resilience to stress will once again allow you to live and fulfilled, functional and healthier life.

If the body is over-stressed for a long while, it is devoting a lot of energy to merely keep you limping along. This energy must be diverted from another need: Exercise, organ function, immune capacity, etc. You might feel generally healthy; perhaps a little off, or maybe just tired… all the while there is vast concert being orchestrated underneath the surface that is trying to maintain homeostasis. The very base of human health, everything considered, is to manage your stress such that your biological account stays deep in the black. Stress management begins with the removal or reduction of as many of the controllable stressors in your life, e.g., improved nutritional choices, start exercising (or stop over-exercising), cease alcohol/tobacco use, etc. Stress management then continues with certain practices that enable you to change your attitude toward life to a more hormetic one. In other words, both physical and psychological stress needs to be attended to. Over time, your biological bank account will grow (you will heal) and your resilience to stress will once again allow you to live and fulfilled, functional and healthier life.

Supporting Literature:

- Black, 2003. (doi:10.1016/S0889-1591(03)00048-5)

- Charmandari, Tsigos, & Chrousos, 2005. (doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.120816)

- Chrousos, 2009. (doi:10.1038/nrendo.2009.106)

- Kyrou & Tsigos, 2009. (doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.08.007)

- McEwen, 2017. (doi: 10.1177/2470547017692328)